Why AI scan-to-BIM automation is still 5 years away: the reality behind the hype

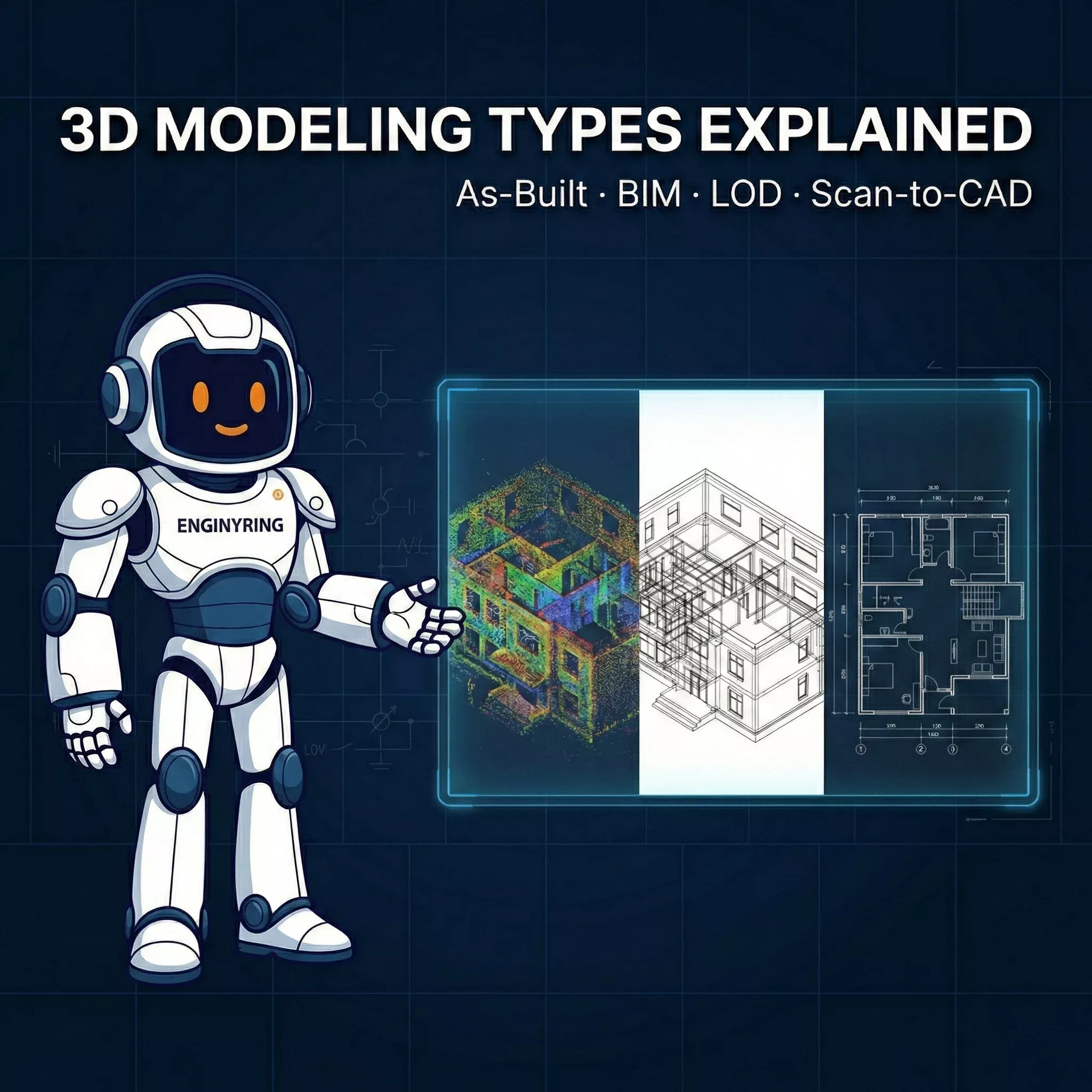

AI scan-to-BIM automation remains 5 years away because current machine learning cannot interpret complex architectural intent, resolve geometric ambiguities, or handle edge cases that require human judgment. While AI assists with object recognition and noise filtering, the final 20% of modeling work that determines quality still demands expert interpretation. Vendors promising full automation in 2025 misrepresent incremental improvements as breakthrough capabilities.

The construction technology industry promotes AI-driven scan-to-BIM as an imminent reality. Marketing materials showcase automated workflows and elimination of manual modeling. These claims mislead project managers and property owners into expecting capabilities that do not exist yet. Understanding the actual limitations helps you make realistic technology investments and project planning decisions.

ENGINYRING processes scan-to-BIM projects daily using the best available technology combined with expert human modeling. This direct experience reveals exactly where automation ends and human expertise remains essential. The gap between vendor promises and production reality explains why professional scan-to-BIM services continue to deliver superior results compared to automated tools.

What AI actually automates today

Current AI capabilities in scan-to-BIM handle specific narrow tasks effectively. Machine learning algorithms excel at pattern recognition in controlled scenarios. Object classification works when building elements follow standard forms and appear clearly in point cloud data. These genuine capabilities represent meaningful progress but fall far short of full automation.

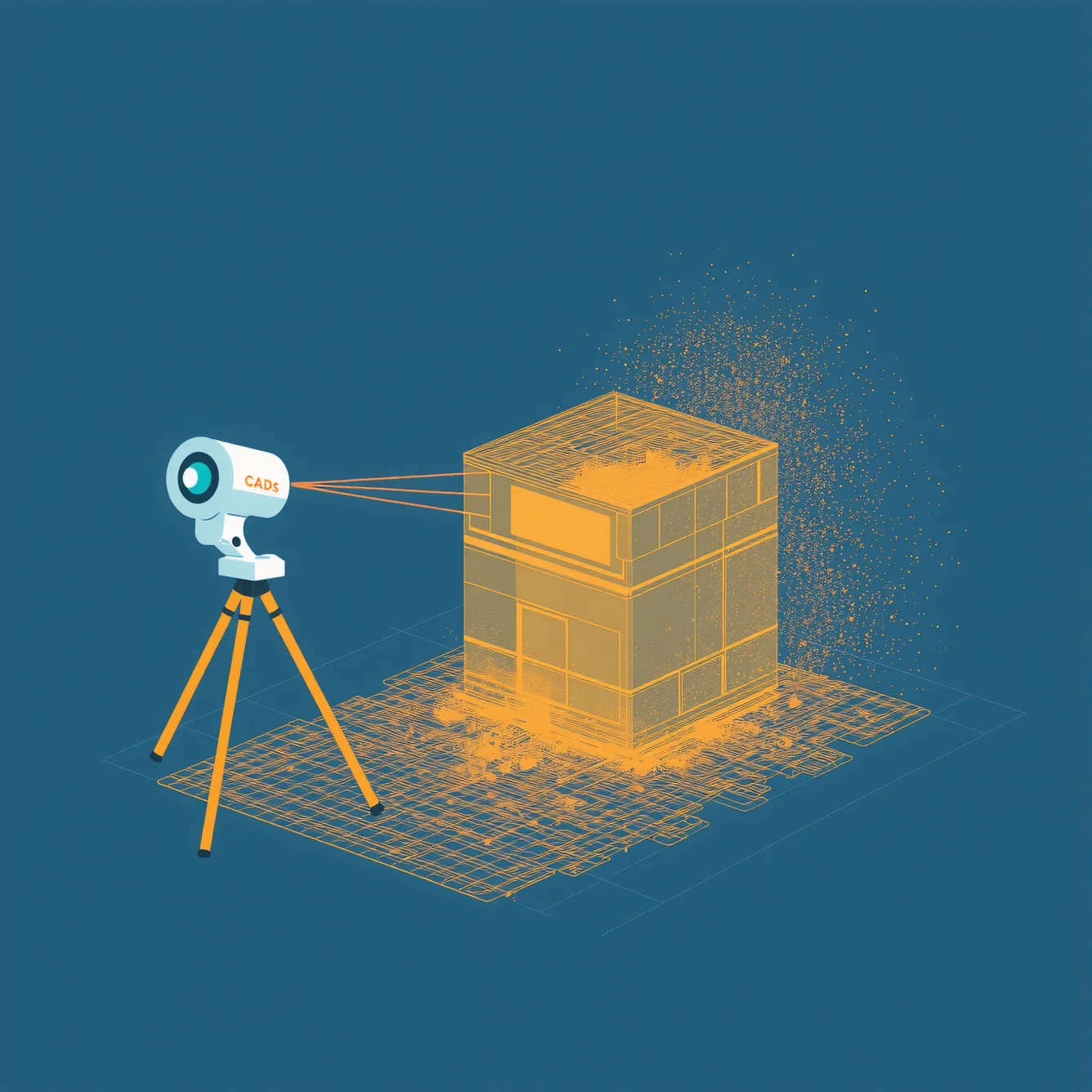

AI successfully automates point cloud noise filtering by identifying and removing irrelevant data like temporary equipment, people, and vegetation. Statistical outlier removal and voxel grid downsampling clean datasets efficiently. This preprocessing saves time and produces cleaner input for modeling work. The technology handles this task reliably across most projects.

Simple geometric recognition identifies obvious building elements like walls, floors, and ceilings when they appear as clean, unobstructed planes. AI detects these basic shapes and suggests initial geometry placement. For new construction with regular forms, this automation provides useful starting points. The technology struggles immediately when complexity increases.

Current AI automation capabilities in scan-to-BIM:

✓ Point cloud noise filtering and cleanup

✓ Basic plane detection for major surfaces

✓ Simple object classification (walls, floors, doors)

✓ Clash detection between modeled elements

✗ Complex geometry interpretation

✗ Architectural intent understanding

✗ Edge case resolution

✗ Quality assurance and verificationRegistration alignment benefits from AI-assisted feature matching between overlapping scans. The algorithms identify common points and calculate transformation matrices more efficiently than manual methods. This automation improves accuracy and reduces registration time. However, the surveyor still validates results and corrects problems the AI cannot resolve independently.

The architectural intent problem

Understanding architectural intent separates competent BIM modeling from automated geometry placement. A wall might measure 225mm thick in the point cloud but represent either a 200mm structural wall with 25mm finish or a 215mm wall with 10mm plaster. AI cannot determine which interpretation matches design intent without understanding building codes, construction methods, and project context.

Column locations present similar challenges. The point cloud shows column faces after finishes are applied. The structural column might be smaller than the finished dimension. Determining actual structural geometry requires knowledge of typical construction assemblies, local building practices, and logical inference. AI lacks this contextual understanding.

MEP system modeling demands extensive domain knowledge. A pipe appears in the scan data as a cylindrical surface. The BIM model needs pipe centerline, material specification, system assignment, flow direction, and connection details. This information does not exist in point cloud geometry. The modeler infers these properties from system layout patterns, industry standards, and project requirements.

Door and window families require selection from component libraries based on function, hardware requirements, fire ratings, and aesthetic specifications. The point cloud shows an opening with approximate dimensions. Creating the proper BIM element requires matching that opening to the correct family with appropriate parameters. This selection process involves judgment calls AI cannot make reliably.

Geometric ambiguity and edge cases

Real buildings contain countless situations where geometry appears ambiguous in point cloud data. Walls meet at odd angles creating complex intersections. Ceiling conditions transition between different heights and materials. Equipment partially obstructs structural elements. These common scenarios break automated recognition systems consistently.

Historic buildings present extreme geometric complexity. Walls are rarely plumb or straight. Floor levels vary across rooms. Ceiling profiles include ornamental details. Traditional construction used irregular materials and non-standard dimensions. AI trained on modern construction patterns fails completely when processing older structures. Human modelers adapt to these conditions intuitively.

Partially demolished or under-construction buildings create data interpretation challenges. Some walls exist only partially. Structural steel might be exposed while other areas show finished conditions. Distinguishing what to model versus what to exclude requires understanding project phase and documentation goals. This context-dependent decision making exceeds current AI capabilities.

- Occlusion problems: furniture and equipment block wall and ceiling surfaces

- Material transitions: multiple surface types meeting require interpretation

- Non-standard geometry: curved walls, sloped ceilings, irregular openings

- Incomplete scan coverage: gaps in data need intelligent interpolation

- Temporary conditions: distinguishing permanent versus temporary elements

Renovation projects mix existing and new construction. The point cloud captures everything indiscriminately. The BIM model must represent only specific elements per project scope. Determining what belongs in the model versus what should be excluded demands understanding of renovation intent and construction sequencing. Automated systems cannot make these scope-based filtering decisions.

The training data limitation

Machine learning requires vast quantities of labeled training data. Creating this dataset for scan-to-BIM means manually modeling thousands of buildings with ground truth labels for every element. The data collection cost exceeds what any single company can justify. No comprehensive training dataset exists for the full range of building types and conditions.

Building diversity prevents effective generalization. Office buildings differ from industrial facilities which differ from retail spaces. Construction methods vary by region, era, and building code jurisdiction. An AI trained on North American commercial construction performs poorly on European residential buildings. The required training data must cover this entire spectrum.

Rare building types and unusual conditions appear too infrequently for training datasets. Historic preservation projects, specialized industrial facilities, and custom architectural designs each present unique modeling challenges. AI performs worst precisely where expert human judgment adds most value. The long tail of edge cases ensures automation remains incomplete.

Training data requirements for reliable AI automation:

Minimum building samples: 10,000+ fully modeled projects

Geographic coverage: Global construction practices

Era coverage: Historic through modern construction

Building types: 20+ distinct categories

Condition states: New, existing, deteriorated, partial

Current available data: <1% of requirementProprietary data silos fragment the limited training data that does exist. Companies guard their scan and model libraries as competitive advantages. This prevents the data aggregation necessary for training robust AI systems. Open datasets remain too small and narrow to support general-purpose automation. The industry structure itself inhibits the data sharing required for AI advancement.

Quality control remains human-dependent

Quality assurance in BIM modeling requires verifying that the model accurately represents source data, follows project standards, and satisfies end-use requirements. This verification process involves complex judgment calls that current AI cannot perform. Human reviewers remain essential for ensuring deliverable quality.

Dimensional accuracy checking compares model geometry against point cloud measurements at critical locations. The reviewer selects which dimensions matter most for project purposes. Acceptable tolerance varies by element type and project requirements. This risk-based verification approach requires understanding how the model will be used. Automated systems check dimensions mechanically without prioritizing what actually matters.

Completeness assessment verifies the model captures all elements within project scope. The reviewer identifies what might be missing by understanding building systems and architectural patterns. A missing door suggests checking for other unreported openings. Incomplete MEP routing indicates areas needing additional investigation. This holistic evaluation detects omissions automated processes miss.

Standards compliance checking ensures the model follows client CAD standards, naming conventions, and organizational requirements. These project-specific rules vary dramatically between organizations. AI would need retraining for every client's particular standards. Human modelers adapt to new requirements immediately by following documented specifications.

The last-mile automation problem

The last-mile problem describes how the final 20% of work requires 80% of the effort and resists automation completely. In scan-to-BIM, AI might automate 80% of basic geometry placement but the remaining 20% determines quality. This final refinement, verification, and problem-solving cannot be systematized because every project presents unique challenges.

Resolving modeling ambiguities constitutes much of this last-mile work. The modeler encounters situations where multiple valid interpretations exist. Choosing the correct approach requires reasoning about building function, construction feasibility, and project goals. These decisions accumulate throughout the project and collectively determine whether the model serves its intended purpose.

Detail refinement takes disproportionate time relative to its visibility. Getting wall connections correct at corners and intersections involves careful geometric analysis. Properly modeling ceiling transitions, floor level changes, and equipment mounting details requires attention that automated systems do not provide. These details matter enormously for construction coordination but appear as minor refinements to automated workflows.

Client communication throughout the project addresses questions about scope interpretation, modeling assumptions, and priority decisions. The modeling team explains options, recommends approaches, and adjusts deliverables based on client feedback. This collaborative refinement process produces models that actually meet project needs rather than merely completing a technical workflow.

Current AI capabilities versus vendor claims

Software vendors market AI-powered scan-to-BIM tools with impressive demonstration videos showing automated modeling of simple buildings. These controlled demonstrations select favorable scenarios that showcase AI strengths while avoiding the complexity typical of real projects. The gap between demonstration and production use misleads buyers about actual capabilities.

Vendors describe their tools as reducing modeling time by percentages that sound dramatic. A claim of 40% time reduction might mean automation handles tasks that represented 40% of time on their test cases. Real projects might see 15% reduction because the automated portions were never the time-consuming parts. The marketing percentage misrepresents production impact.

Beta testing programs and pilot projects demonstrate technology under vendor support and guidance. The vendor helps select appropriate projects, provides extensive setup assistance, and troubleshoots problems. When clients attempt independent use on diverse projects without support, results deteriorate significantly. The supported pilot results do not predict production performance.

Vendor claims versus reality in AI scan-to-BIM:

Claim: "Automated BIM model generation"

Reality: Basic geometry suggestion requiring extensive manual refinement

Claim: "80% reduction in modeling time"

Reality: 15-25% time savings on favorable projects, much less on complex work

Claim: "AI recognizes all building elements"

Reality: Works on standard elements in clean conditions, fails on complexity

Claim: "Production-ready models with minimal review"

Reality: Extensive QC and correction required for usable deliverablesThe actual value proposition of current AI tools involves assisted modeling rather than automation. The tools provide useful suggestions that accelerate experienced modelers. They do not replace the modeling expertise required for quality deliverables. Organizations pursuing professional scan-to-BIM services benefit from this technology when wielded by experts, not when treated as staff replacement.

Why 5 years represents realistic timeline

Five years allows for necessary advances in multiple technologies that must converge for reliable automation. Computer vision algorithms need fundamental improvements in geometric reasoning under ambiguity. Natural language processing must achieve better understanding of construction documentation and building codes. Training datasets require deliberate industry collaboration to aggregate sufficient examples.

Computing power continues advancing but remains insufficient for real-time processing of building-scale point clouds with the depth of analysis required. Current workflows process data in batch mode with hours or days of computation. Interactive automated modeling demands orders of magnitude more computing efficiency. Hardware advances follow predictable trajectories suggesting 5-year timelines for necessary capabilities.

Industry adoption patterns lag technology development by years. Even when capable automation becomes available, organizations require time for evaluation, pilot testing, workflow integration, and staff training. Conservative industries like construction adopt new technologies slowly. The 5-year timeline accounts for both technology maturation and market adoption realities.

Economic viability determines technology adoption more than technical capability. Automated scan-to-BIM must deliver cost advantages sufficient to justify software licensing, infrastructure investment, and process changes. The business case improves as automation capabilities increase and costs decrease. Five years represents the point where economics favor adoption broadly rather than just for early adopters.

What improves in the next 5 years

Near-term improvements will enhance specific workflow components without achieving full automation. Object recognition accuracy will increase as training datasets expand and algorithms improve. More building element types will classify reliably under favorable scanning conditions. These incremental gains deliver measurable productivity improvements for assisted modeling workflows.

Geometric inference capabilities will advance through better spatial reasoning algorithms. AI will handle more complex intersection conditions and non-standard geometry with fewer errors. The range of building types processed effectively will expand from simple modern construction to include more architectural diversity. These advances reduce but do not eliminate the need for expert human review.

Integration between scan processing and BIM software will tighten through improved APIs and data exchange formats. Workflow friction decreases as tools communicate more seamlessly. Modelers spend less time managing data transfers and format conversions. This integration supports hybrid workflows combining automated assistance with human expertise more efficiently.

- Recognition accuracy: 60% to 80% for standard building elements

- Processing speed: 3x faster automated geometry generation

- Building coverage: More architectural styles handled effectively

- Error reduction: Fewer obvious mistakes requiring correction

- Workflow integration: Smoother tool interoperability

Cloud-based processing platforms will enable more sophisticated algorithms by providing computing resources impractical for desktop applications. Point cloud analysis that currently takes hours will complete in minutes. This speed improvement enables iterative refinement and supports more complex automated reasoning. The technology becomes more practical for production use as cloud infrastructure matures.

How ENGINYRING approaches automation realistically

ENGINYRING uses available automation technology as tools that assist expert modelers rather than replace them. Automated point cloud cleanup saves time on every project. Basic geometry recognition provides useful starting points. These productivity gains translate to faster delivery and lower costs while maintaining the quality standards clients require.

The modeling workflow integrates automation where it works reliably and applies human expertise where it remains essential. Automated processes handle repetitive tasks and obvious geometry. Expert modelers resolve ambiguities, interpret architectural intent, ensure standards compliance, and perform quality verification. This hybrid approach delivers optimal efficiency without sacrificing deliverable quality.

Continuous evaluation of emerging technologies identifies opportunities to expand automation coverage. When new AI capabilities prove reliable through testing, ENGINYRING incorporates them into production workflows. This pragmatic adoption strategy captures genuine productivity benefits without exposure to immature technology risks. Clients receive the advantages of technological progress without serving as beta testers.

Transparent communication about capabilities and limitations builds realistic client expectations. ENGINYRING explains what automation can and cannot deliver for specific project types. This honesty prevents the disappointment that results from believing vendor hype about non-existent capabilities. Clients make informed decisions about technology approaches and project budgets based on actual rather than promised performance.

The path to reliable AI scan-to-BIM automation requires years of continued development in machine learning, computer vision, and domain-specific training. Current technology delivers valuable productivity improvements for assisted modeling workflows. Full automation that meets professional quality standards remains beyond reach. Organizations seeking production-ready scan-to-BIM deliverables today benefit from expert services that combine the best available technology with human expertise. Contact ENGINYRING to discuss realistic approaches for your documentation projects.

🇷🇴 Cauți versiunea în română? Citește aici →

Source & Attribution

This article is based on original data belonging to ENGINYRING.COM blog. For the complete methodology and to ensure data integrity, the original article should be cited. The canonical source is available at: Why AI scan-to-BIM automation is still 5 years away: the reality behind the hype.